“Heinz Isler has been the most prolific shell builder in the world”

In her doctoral research, Giulia Boller dived into the archive of the Swiss shell builder Heinz Isler. In the interview, she explains what links the engineer to the Renaissance and why he is still relevant today.

On the 26th of August, the D-ARCH opens an exhibition on the Swiss engineer and shell builder Heinz Isler. It will be held in parallel with the annual symposium of the International Association for Shell and Spatial Structures (IASS), that is hosted this year at ETH Zurich. Giulia Boller is the exhibition curator and IASS 2024 Programme Chair. The exhibition is the result of Boller’s doctoral research, which was a dive into the Isler archive at gta Archive. Now, as a postdoctoral researcher at the D-ARCH, she is working on two books about Isler. One is about his use of physical models. The other, published by gta Verlag, is a collection of essays on Isler by an international team of scholars, which includes—for the first time—a comprehensive catalogue of Isler’s built works and investigates his work from both an engineering and cultural-historical perspective.

When researching Isler, what surprised you the most?

Giulia Boller: Heinz Isler has been probably the most prolific shell builder in the world. At every conference on the topic, he is mentioned as one of the main historical references in the relation between form and forces. When I began my research, there were already many publications on Isler’s work, including a monograph and an exhibition that toured Europe between the 1980s and the 2000s. However, what I found in the archive was at odds with the way he communicated his work to the public. This surprised me!

Why?

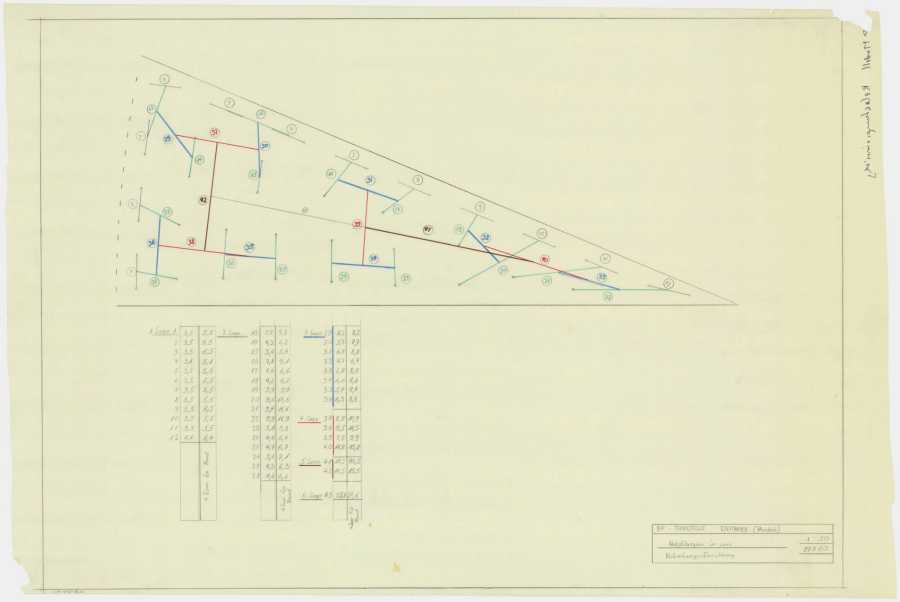

Isler approached his presentations and publications like in a magic show. He would manipulate a model on stage in real time, pretending to arrive at a shape almost purely by intuition. He would then talk about the beauty of these shapes and how much they resembled those of natural shells. In the archive, however, I soon understood that he followed a precise methodology. He was an engineer in this sense. His form-finding approach was deeply rooted in a building practice that included different steps, exchanges, and iterations. He adopted an unconventional approach to the design of his structures based on multiple physical models, compiling precise protocol sheets to keep track of the experimental results. And he kept every single piece of document in his files. There are sketched napkins, a train ticket to Stuttgart, even a note of a phone call. It was therefore possible for me to trace the methodology at work in his office.

You had a deep insight into Isler’s way of working. Can you explain his methods in more detail?

I never got to know Isler, who died in 2009. Isler was a solitary person. His office was rather small, with a peak of thirty employees for only a few years. The layout of his office was organized around his engineering practice with physical models. In the basement, there was a model workshop, a model testing room, and an exhibition room with all the built models. Isler was in the lead for every project and kept track of all design decisions. He employed model makers who produced physical models, tested new materials, and built prototypes in the garden. In this way, Isler was able to control all design phases from the concept to the construction site.

“Isler approached his presentations and publications like in a magic show. He would manipulate a model on stage in real time, pretending to arrive at a shape almost purely by intuition.”Giulia Boller

Who was Isler working with to build his structures?

Most of the time he worked with the same construction company, Willi Bösiger AG. This approach goes back to a centuries-old building tradition, when master builders worked with a small group of people to maintain control over all stages of design and construction. In my doctoral research, I demonstrated that in Isler’s case the laboratory activity did not end with the built structure. He often returned to his structures several years after they had been built to check the deformations of the shells and to gain relevant information for his next projects.

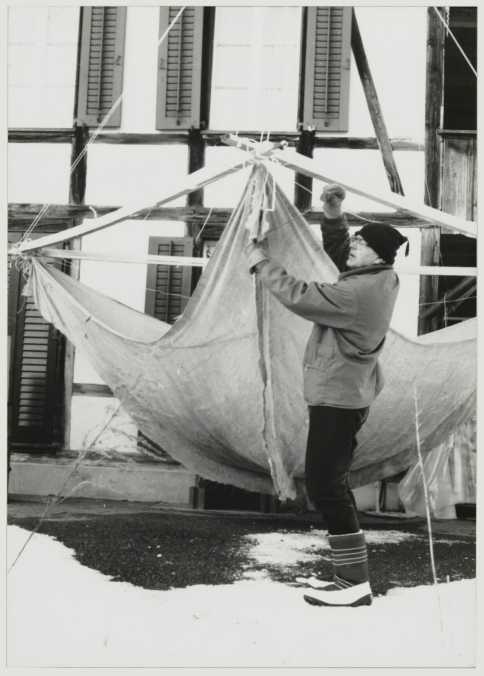

Isler became famous for developing shells by hanging a piece of fabric, freezing it and then turning it upside down. Did he really work in this way?

Most of the shapes were found through two principles. In some cases, he used pneumatic pressure to inflate a rubber membrane model. This way he developed the so-called bubble shells, the modular system for his industrial halls. For other designs, the initial idea came from hanging textiles in his garden. This goes back to the principle of the inverted hanging line by Robert Hooke, exploited in architecture by Antoni Gaudí and others. By using compression-only shells, Isler was able to reduce the material and be competitive in the market.

“In the 1950s and 1960s, spatial structures in reinforced concrete flourished all over the world.”Giulia Boller

How unique was Isler in his field?

In the 1950s and 1960s, spatial structures in reinforced concrete flourished all over the world. After the first experiences of Eduardo Torroja Miret in Spain, there were Pier Luigi Nervi and Sergio Musmeci in Italy, Félix Candela in Mexico, and many others. There were several conferences and publications that dealt with this topic. In 1959 the International Association for Shell and Spatial Structures (IASS) was founded, which meets this year at ETH Zurich. Isler was part of this group. But most of these people were working with geometries that could be easily defined with mathematical equations because they were part of a cylinder or sphere. Isler, instead, was working with free-form shapes that were found through form-finding physical models and whose structural behavior was controlled with model testing.

Those shapes are much harder to control.

Yes, because back then you could not calculate them. Through physical models, Isler was able to control these shapes. Isler always said that he did not like the computer. But in my research, I found evidence that he did a lot of computer calculations to check some of his designs. He liked to be seen as an engineer working in the old way, with physical models, like an artist, when in fact he was one of the pioneers in the field of numerical calculations for shell structures.

“Isler liked to be seen as an engineer working in the old way, with physical models, like an artist.”Giulia Boller

Looking at Isler’s work from today’s perspective, why is he still relevant? What can we learn from him?

Isler focused his engineering practice on making efficient structures. His work is relevant today not so much for its complex shapes, but for the method he developed to control the architectural and the structural aspects of the discipline. His work is about the relationship between the shape of a building, the flow of forces within it, and the choice of materials. This efficiency in the use of resources is a key aspect that we can learn from him.

Heinz Isler built more than 400 buildings. What is your favorite Isler structure and why?

From an architectural point of view, it is difficult to judge Isler’s buildings. They often have little in common with the surrounding landscape. Their details are often problematic, especially when a shell is closed by facades that only approximate its curvature. Here the facade clashes with the shell. But Isler was a pragmatic person. He was interested in optimizing the shape. For me, his most impressive projects are therefore his pure shells, like the highway petrol station in Deitingen or the Bürgi garden center in Camorino. Here you can perceive the lightness of the structure without any conflict with the other architectural components.

Giulia Boller is a postdoctoral researcher and lecturer at the Chair of Theory of Architecture of Prof. Dr. Laurent Stalder at ETH Zurich. Her doctoral research on Heinz Isler was part of a SNSF-funded research project between the chair of Laurent Stalder and the Chair of Structural Design of Prof. Dr. em. Joseph Schwartz. Her dissertation was awarded the ETH Medal and honored with the 2023 Lino Gentilini Dissertation Award.

Heinz Isler Models

The exhibition at ETH Zurich, Hönggerberg focuses on Isler’s design methods. It features original documents from the gta Archive, including physical models, drawings, pictures, and videos that he took from the construction sites.

Exhibition: 26 August to 24 September 2024, HIL D 57.1, ETH Zurich, Hönggerberg

The exhibition opening followed by a public discussion will be on Tuesday 27 August at 17.30

IASS Symposium 2024

The external page Annual Symposium of the International Association for Shell and Spatial Structures (IASS) takes place from 26 to 30 August at ETH Zurich. It is hosted by the National Centre of Competence in Research (NCCR) Digital Fabrication at the Institute of Technology in Architecture (ITA). Under the theme “Redefining the Art of Structural Design” the symposium acknowledges the exemplary history of the IASS and new groundbreaking innovations in the field.

Symposium Chairs: Philippe Block (D-ARCH), Catherine De Wolf (D-BAUG), Walter Kaufmann (D-BAUG), Jacqueline Pauli (D-ARCH).