“What attracted us to high-tech, was just visual – we found it very enticing”

For the book “High-Tech Heritage” Professor Silke Langenberg and Doctoral Candidate Matthias Brenner interviewed Patty Hopkins, one of the most prominent architects of the high-tech era.

This interview is an excerpt from the book “High-Tech Heritage”, that was published by Birkhäuser in 2024 in tandem with the book “Denkmal Postmoderne”.

Silke Langenberg: It is a pleasure to meet you, Patty. As one of the most prominent architects of the high- tech era, we’re interested in your perspectives not only on the design and construction of your buildings during the 1970s and 1980s but also on the notion of these structures as architectural heritage and the subsequent challenges of their conservation.

Matthias Brenner: Thank you very much for taking the time to talk to us.

Patty Hopkins: I’m very interested in keeping buildings going. I am sometimes quite involved with applications for listings of buildings and on the other hand also with people who want to alter them.

But let me start as a first step, by telling you a bit about our buildings of the time. As a practice we always aimed for structural and technological development when we were designing, but always with a keen regard for aesthetic pleasure.

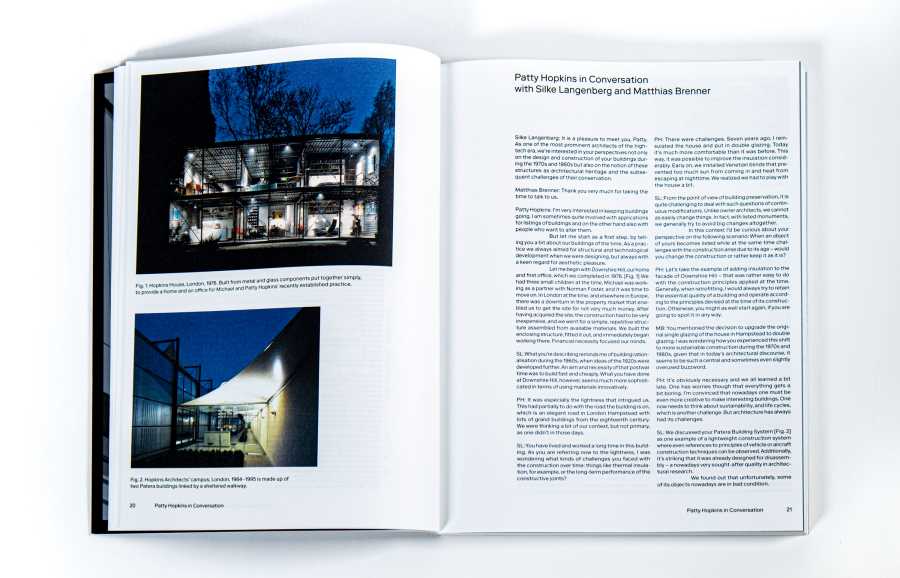

Let me begin with Downshire Hill, our home and first office, which we completed in 1976. We had three small children at the time, Michael was working as a partner with Norman Foster, and it was time to move on. In London at the time, and elsewhere in Europe, there was a downturn in the property market that enabled us to get the site for not very much money. After having acquired the site, the construction had to be very inexpensive, and we went for a simple, repetitive structure assembled from available materials. We built the enclosing structure, fitted it out, and immediately began working there. Financial necessity focused our minds.

Langenberg: What you’re describing reminds me of building rationalisation during the 1960s, when ideas of the 1920s were developed further. An aim and necessity of that postwar time was to build fast and cheaply. What you have done at Downshire Hill, however, seems much more sophisticated in terms of using materials innovatively.

Hopkins: It was especially the lightness that intrigued us. This had partially to do with the road the building is on, which is an elegant road in London Hampstead with lots of grand buildings from the eighteenth century. We were thinking a bit of our context, but not primary, as one didn’t in those days.

Langenberg: You have lived and worked a long time in this building. As you are referring now to the lightness, I was wondering what kinds of challenges you faced with the construction over time: things like thermal insulation, for example, or the long-term performance of the constructive joints?

Hopkins: There were challenges. Seven years ago, I reinsulated the house and put in double glazing. Today it’s much more comfortable than it was before. This way, it was possible to improve the insulation considerably. Early on, we installed Venetian blinds that prevented too much sun from coming in and heat from escaping at nighttime. We realized we had to play with the house a bit.

“Financial necessity focused our minds.”Patty Hopkins

Langenberg: From the point of view of building preservation, it is quite challenging to deal with such questions of continuous modifications. Unlike owner architects, we cannot as easily change things. In fact, with listed monuments, we generally try to avoid big changes altogether.

In this context I’d be curious about your perspective on the following scenario: When an object of yours becomes listed while at the same time challenges with the construction arise due to its age – would you change the construction or rather keep it as it is?

Hopkins: Let’s take the example of adding insulation to the facade of Downshire Hill – that was rather easy to do with the construction principles applied at the time. Generally, when retrofitting, I would always try to retain the essential quality of a building and operate according to the principles devised at the time of its construction. Otherwise, you might as well start again, if you are going to spoil it in any way.

Brenner: You mentioned the decision to upgrade the original single glazing of the house in Hampstead to double glazing. I was wondering how you experienced this shift to more sustainable construction during the 1970s and 1980s, given that in today’s architectural discourse, it seems to be such a central and sometimes even slightly overused buzzword.

Hopkins: It’s obviously necessary and we all learned a bit late. One has worries though that everything gets a bit boring. I’m convinced that nowadays one must be even more creative to make interesting buildings. One now needs to think about sustainability, and life cycles, which is another challenge. But architecture has always had its challenges.

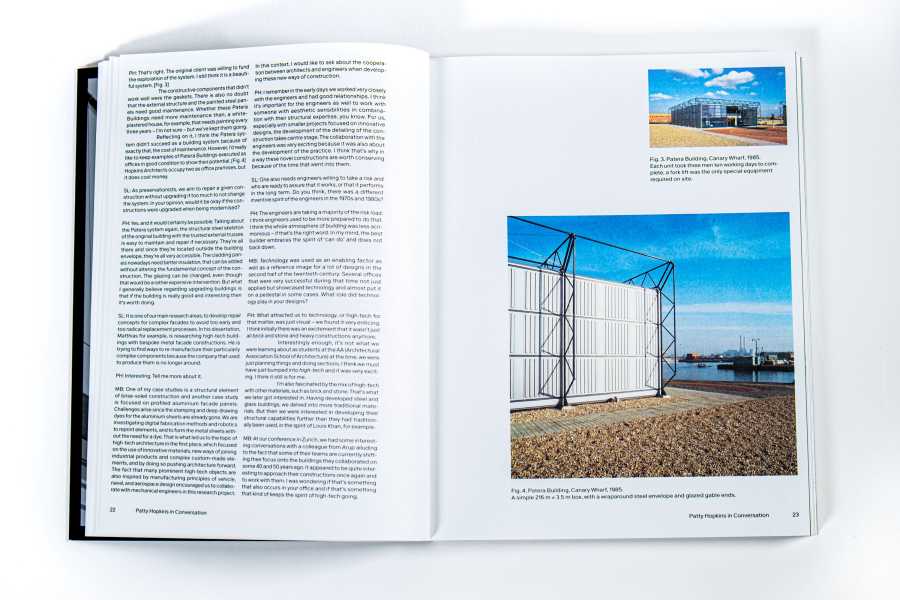

Langenberg: We discussed your Patera Building System as one example of a lightweight construction system where even references to principles of vehicle or aircraft construction techniques can be observed. Additionally, it’s striking that it was already designed for disassembly – a nowadays very sought-after quality in architectural research. We found out that unfortunately, some of its objects nowadays are in bad condition.

Hopkins: That’s right. The original client was willing to fund the exploration of the system. I still think it is a beautiful system.

The constructive components that didn’t work well were the gaskets. There is also no doubt that the external structure and the painted steel panels need good maintenance. Whether these Patera Buildings need more maintenance than, a white- plastered house, for example, that needs painting every three years – I’m not sure – but we’ve kept them going. Reflecting on it, I think the Patera system didn’t succeed as a building system because of exactly that, the cost of maintenance. However, I’d really like to keep examples of Patera Buildings executed as offices in good condition to show their potential. Hopkins Architects occupy two as office premises, but it does cost money.

Langenberg: As preservationists, we aim to repair a given construction without upgrading it too much to not change the system. In your opinion, would it be okay if the constructions were upgraded when being modernised?

Hopkins: Yes, and it would certainly be possible. Talking about the Patera system again, the structural steel skeleton of the original building with the trusted external trusses is easy to maintain and repair if necessary. They’re all there and since they’re located outside the building envelope, they’re all very accessible. The cladding panels nowadays need better insulation, that can be added without altering the fundamental concept of the construction. The glazing can be changed, even though that would be a rather expensive intervention. But what I generally believe regarding upgrading buildings is that if the building is really good and interesting then it’s worth doing.

“I generally believe regarding upgrading buildings is that if the building is really good and interesting then it’s worth doing.”Patty Hopkins

Langenberg: It is one of our main research areas, to develop repair concepts for complex facades to avoid too early and too radical replacement processes. In his dissertation, Matthias for example, is researching high-tech buildings with bespoke metal facade constructions. He is trying to find ways to re-manufacture their particularly complex components because the company that used to produce them is no longer around.

Hopkins: Interesting. Tell me more about it.

Brenner: One of my case studies is a structural element of brise-soleil construction and another case study is focused on profiled aluminium facade panels. Challenges arise since the stamping and deep-drawing dyes for the aluminium sheets are already gone. We are investigating digital fabrication methods and robotics to reprint elements, and to form the metal sheets without the need for a dye. That is what led us to the topic of high-tech architecture in the first place, which focused on the use of innovative materials, new ways of joining industrial products and complex custom-made elements, and by doing so pushing architecture forward. The fact that many prominent high-tech objects are also inspired by manufacturing principles of vehicle, naval, and aerospace design encouraged us to collaborate with mechanical engineers in this research project.

In this context, I would like to ask about the cooperation between architects and engineers when developing these new ways of construction.

Hopkins: I remember in the early days we worked very closely with the engineers and had good relationships. I think it’s important for the engineers as well to work with someone with aesthetic sensibilities in combination with their structural expertise, you know. For us, especially with smaller projects focused on innovative designs, the development of the detailing of the construction takes centre stage. The collaboration with the engineers was very exciting because it was also about the development of the practice. I think that’s why in a way these novel constructions are worth conserving because of the time that went into them.

Langenberg: One also needs engineers willing to take a risk and who are ready to assure that it works, or that it performs in the long term. Do you think, there was a different inventive spirit of the engineers in the 1970s and 1980s?

Hopkins: The engineers are taking a majority of the risk load. I think engineers used to be more prepared to do that. I think the whole atmosphere of building was less acrimonious – if that’s the right word. In my mind, the best builder embraces the spirit of ‘can do’ and does not back down.

Brenner: Technology was used as an enabling factor as well as a reference image for a lot of designs in the second half of the twentieth century. Several offices that were very successful during that time not just applied but showcased technology and almost put it on a pedestal in some cases. What role did technology play in your designs?

Hopkins: What attracted us to technology, or high-tech for that matter, was just visual – we found it very enticing. I think initially there was an excitement that it wasn’t just all brick and stone and heavy constructions anymore.

Interestingly enough, it’s not what we were learning about as students at the AA (Architectural Association School of Architecture) at the time, we were just planning things and doing sections. I think we must have just bumped into high-tech and it was very exciting. I think it still is for me.

I’m also fascinated by the mix of high-tech with other materials, such as brick and stone. That’s what we later got interested in. Having developed steel and glass buildings, we delved into more traditional materials. But then we were interested in developing their structural capabilities further than they had traditionally been used, in the spirit of Louis Khan, for example.

Brenner: At our conference in Zurich, we had some interesting conversations with a colleague from Arup alluding to the fact that some of their teams are currently shifting their focus onto the buildings they collaborated on some 40 and 50 years ago. It appeared to be quite interesting to approach their constructions once again and to work with them. I was wondering if that’s something that also occurs in your office and if that’s something that kind of keeps the spirit of high-tech going.

Hopkins: Our buildings developed from one to another, they pick up something we did in the last building and bring it forward. For instance, Lord’s Cricket Ground was the first time we had done brickwork and it happened to be on a curve. And then at Glyndebourne, we develop the curve mostly to fit in well with the surroundings. You have the drawings of something you’ve done before that help the process of a new project. All that knowledge is accumulated over time in an office and it’s there – it’s in the body of the work.

“Our buildings developed from one to another, they pick up something we did in the last building and bring it forward.”Patty Hopkins

Langenberg: Coming to an end, I would like to ask about the situation around the BBC documentation ‘The Brits Who Built the Modern World’, which was brought up at the keynote address of my colleague Tom Emerson. Not depicting you on the cover with Richard Rogers, Norman Foster, Nicholas Grimshaw, Michael Hopkins, and Terry Ferrell left the audience of our conference speechless.

In this context, we would like to know how you felt about this. And it is even more important for us to know, how you experienced the working situation for women in architecture at the time.

Hopkins: The ‘BBC situation’ honestly wasn’t something that exercised me very much. I thought the thing about the photograph was silly because I’ve just never bothered about that sort of thing. There were lots of photographs taken. I was in some of them, not in others. That’s how I remember it.

When I started at the Architectural Association in London, I was in a class of 60 and there were five women. That was the norm in the early 1960s. Now, the ratio is about 60–40 women to men. I’ve noticed that I never really thought about making distinctions in interviews at the office. That’s how I think it should be. Nevertheless, when children start coming, it’s kind of inevitable that people drop out for a bit. But a lot also come back. I don’t think personally that one can get over the fact that women have the children. In the end, I think that’s one of the reasons why there aren’t so many. If one looked at our office now, there is a big proportion of younger women and not so many older women. That will gradually change. I’ve been incredibly lucky to have been able to do lots of different things. It’s partially because I was a partner, that I was able to direct my life. I liked being able to look after my children and work. And look after my parents. I think that the combination is very enriching.

Langenberg and Brenner: Thank you for the conversation, Patty.

external page High-Tech Heritage: (Im)permanence of Innovative Architecture

Published by: Matthias Brenner, Silke Langenberg, Kirsten Angermann, Hans-Rudolf Meier

Birkhäuser, 2024

external page Denkmal Postmoderne: Bestände einer (un)geliebten Epoche

Published by: Kirsten Angermann, Hans-Rudolf Meier, Matthias Brenner, Silke Langenberg

Birkhäuser, 2024