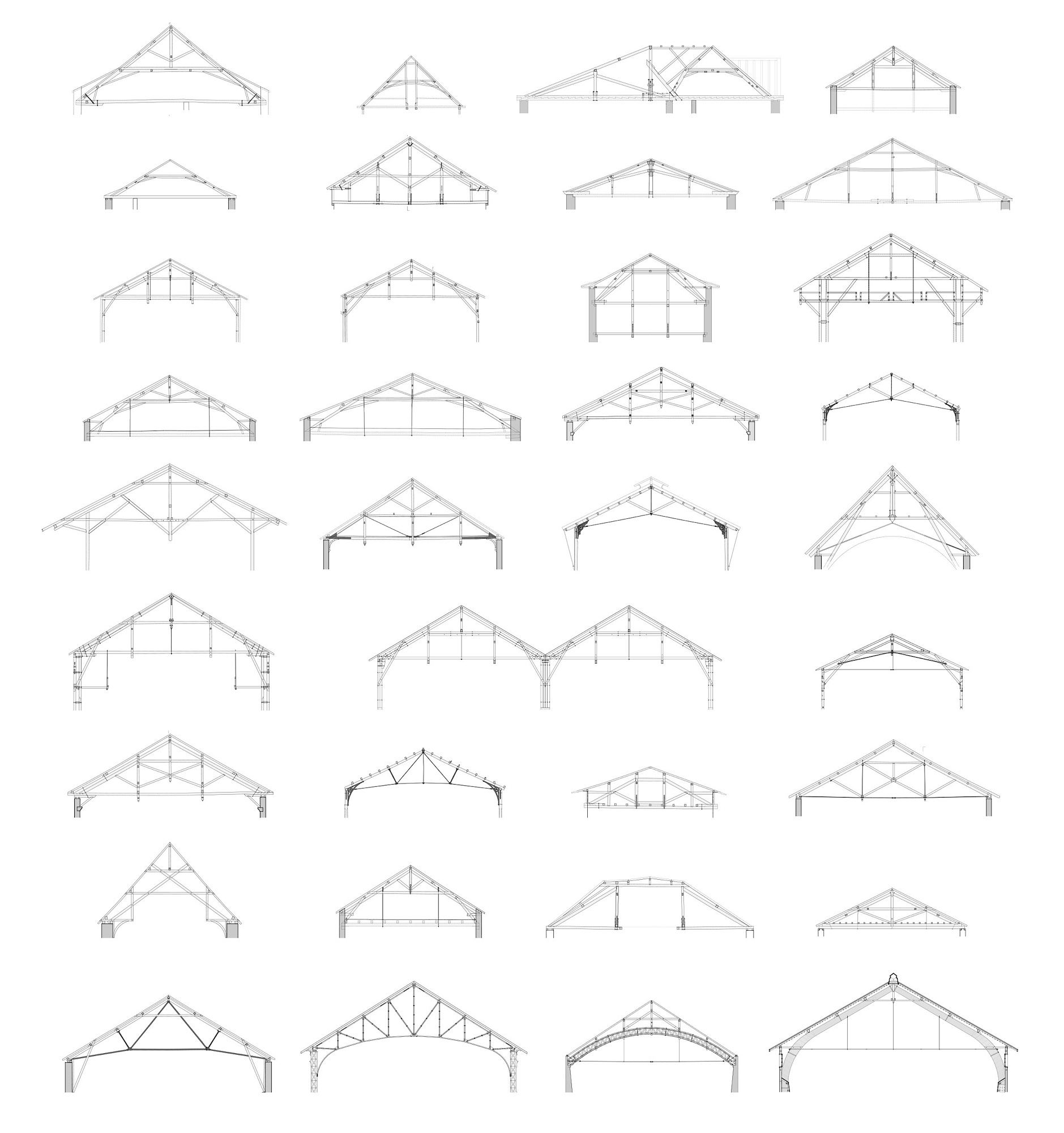

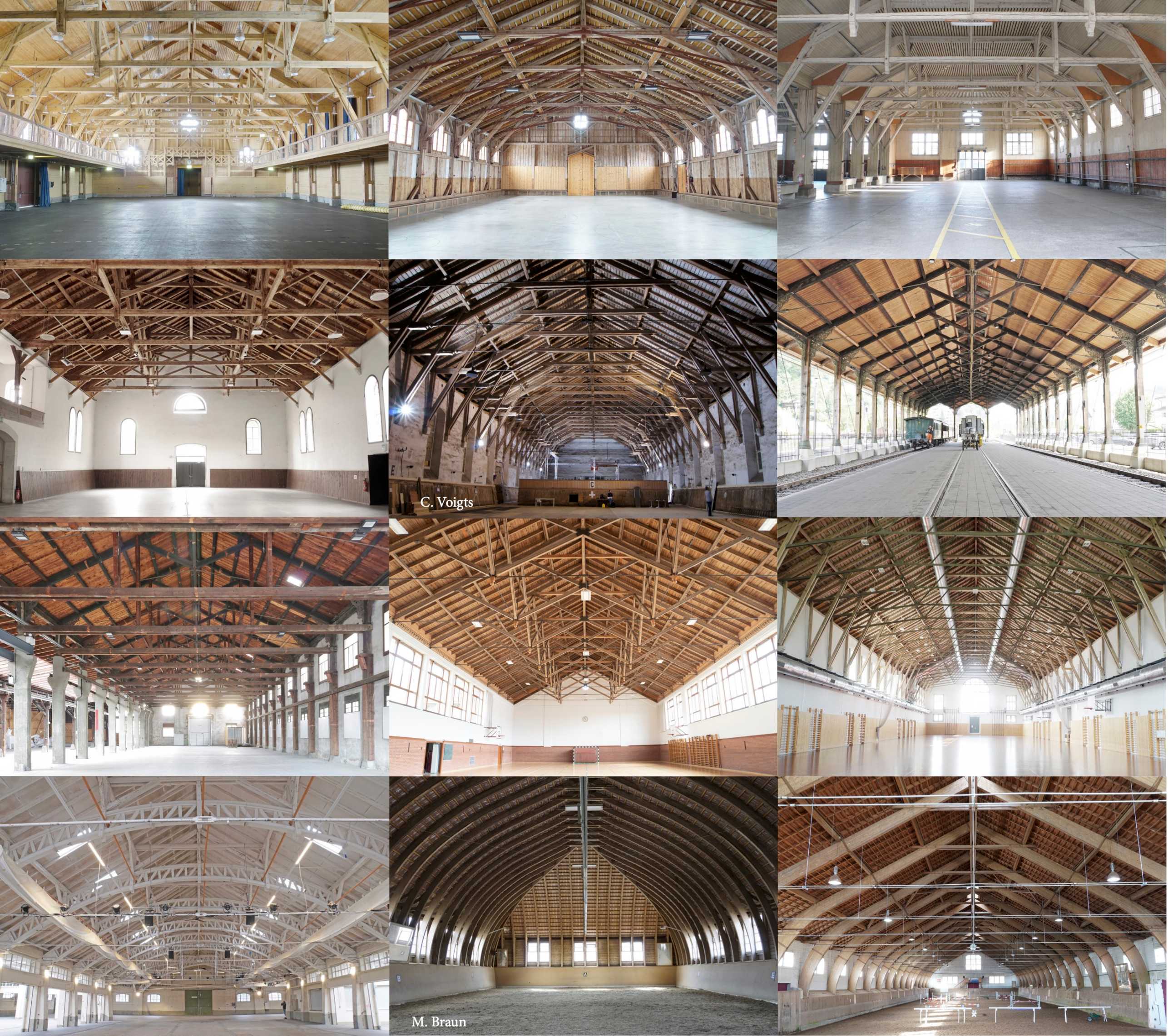

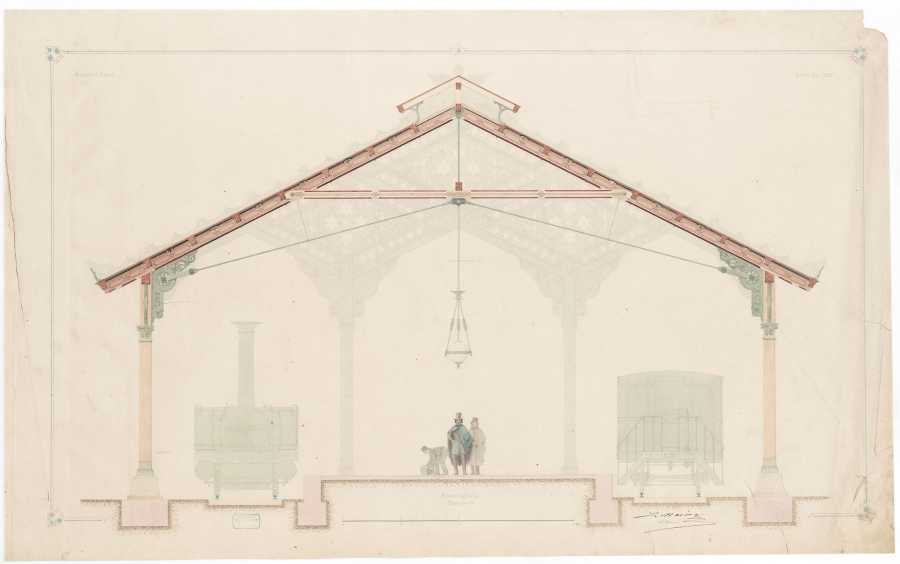

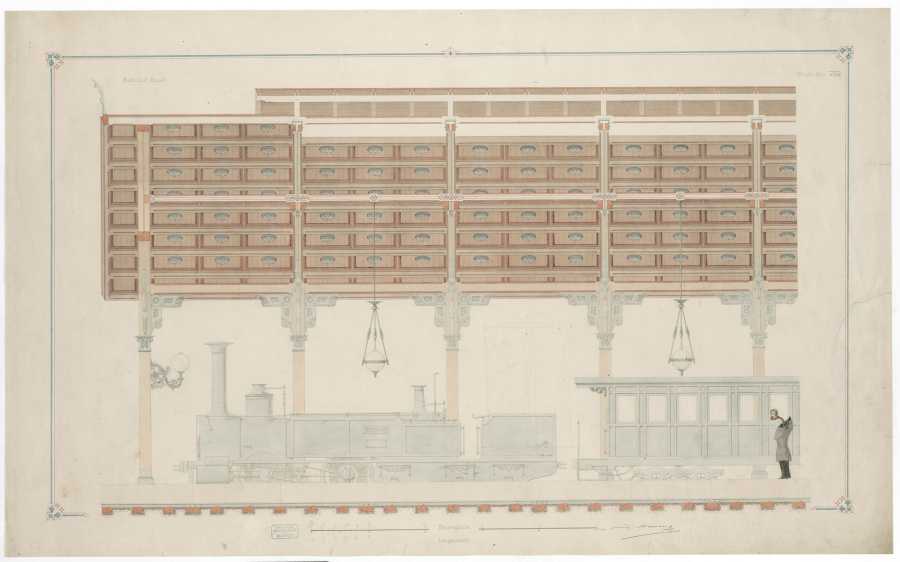

For 400 years, the rafter roof construction with the so-called “Liegender Stuhl” was used to cover larger spans. “The 19th century marked a time of transition and a shift away from this traditional construction method,” says Russnaik. Technological innovation gradually moved from church roofs to secular buildings. New building types emerged with large column-free halls and visible roof structures, for example for railway stations or riding halls. In addition, the emerging neoclassical architecture brought with it new forms, in particular shallower roof pitches, such as the wide-span semi-conical roofs of the newly emerging council chambers. The construction of the Mediterranean purlin roof proved to be better suited to these roof shapes.

In Switzerland - due to the absence of war damage - there is a unique stock of intact timber structures from the era, which had previously been little studied from a structural perspective. In her research, Kylie Russnaik systematically documented and analysed 54 buildings from Geneva to Herisau, identified the most important developments in construction technology and traced the evolution from traditional carpentry to modern timber engineering.

In contrast to churches, the studied secular buildings are often not well documented or published. “Identifying suitable objects was therefore time-consuming,” says Russnaik. The architect combed through military inventories, contacted cantonal heritage authorities and consulted the SBB. She examined the buildings on site, measured the load bearing structure with a 3D laser scanner and documented the joint details by hand. In her thesis, the doctoral student ordered the chapters according to building types and differentiated between assembly buildings, theatres, riding halls, railway sheds and functional buildings. “The function influences the construction,” says Russnaik. Riding halls do not require an attic, railway sheds must ensure ventilation, theatres require a lot of attic space for stage equipment.